Game Of Thrones Finale Was Good (& The Only Way To End The Show)

Game Of Thrones’ Finale Was Good (& The Only Way To End The Show)

Contents

Game of Thrones’ series finale has proven divisive, but there really was no other way for the show to end. We explain how it all fits together.

You Are Reading :[thien_display_title]

Game of Thrones’ ending may come after a divisive final season and leave many questions behind, but it’s difficult to think of another way the series could’ve ended without betraying its central premise and themes.

The Game of Thrones series finale, “The Iron Throne,” saw Daenerys finally reach her goal and win her place as ruler of Westeros. But destruction she left in her wake, combined with her intention to pursue rule of the known world convinced Jon and Tyrion that she was a more dangerous ruler than any they’d faced before. She was cut down by her lover in front of the throne she’d dedicated her life to winning. In the wake of her death, a new system of government designed to protect the now Six Kingdoms of Westeros was put in place, choosing rulers by council and naming Bran the Broken as their first leader.

There’s no denying that Game of Thrones season 8 had problems. Only six episodes were dedicated to wrapping up countless subplots, and the added load of trying to justify Dany’s ultimate descent into madness made the task a near impossible one. But despite the very valid criticisms laid at the show’s execution in it its final hours, wrapping the story up any differently, at least when it came to the narrative choices, wouldn’t have made sense in the greater context of Game of Thrones’ as a whole.

Jon & Danerys’ Story Could Only End This Way

While Game of Thrones season 7 had Jon Snow and Daenerys Targaryen meet, ally with each other and fall in love, season 8 saw Jon faced with the differences in their leadership. When he and Dany arrive at Winterfell, it’s not long before the truth about her execution of the Tarlys comes out and Sam furiously points out to Jon that when faced with similar decisions, Jon had chosen mercy more often than not. The only time he’d ever chosen to engage in capital punishment was after his own murder and resurrection, and even then, the act left such a bitter taste in his mouth, he left the Night’s Watch immediately after. Even after killing Dany, he doesn’t protest a return to the Wall when it’s all over as punishment. Compared with Dany’s history of glorious vengeance via fire and blood, despite being cloaked in her genuine intentions to liberate those who suffered under tyrants, Jon’s distaste for that kind of violence and his largely successful avoidance of it as a leader threw into sharp relief the irreconcilable differences between the two.

Jon’s immediate refusal to embrace his name and destiny as true heir to the Iron Throne is another foundational disparity between him and Dany, and one that had further-reaching thematic implications than their diverging feelings about war and vengeance. Since season 1, the Game of Thrones narrative has warned us that those who chase power for the sake of it or because they feel divinely entitled to it don’t make for good leaders. While Ned’s inability to manage the politics of King’s Landing ultimately got him killed, he’d have been a more effective ruler than Robert, Joffrey and Cersei had he been given the chance; there’s no question his honesty and lack of ego would’ve served the Realm better than Robert’s inattentiveness, Joffrey’s sociopathy, Tommen’s naïvete and Cersei’s bloodlust. Varys says as much to him in “Baelor” when he visits Ned in the Black Cells.

And while Dany’s pursuit of power has its roots in survival and agency – both of which are elements that made her heroic for a very long time – ultimately, she proved more committed to strengthening her own position and punishing any who would oppose her than she was to the welfare of those who could not defend themselves. While her descent proved too quick and blunt to hold water with many viewers, not to mention the problematic optics of having a woman’s fate decided by two men who assume they know better than her, ultimately the show had its say about rulers who chase power a long time ago.

The comparison between Jon and Dany is certainly not for everyone, but the past eight seasons have clearly been spent tracing the paths of two kinds of leaders – one who loathed killing and rarely jumped at the chance to do it and one whose taste for vengeance and power had been intensified exponentially the more losses she suffered, be they friends, dragons, battles or pride.

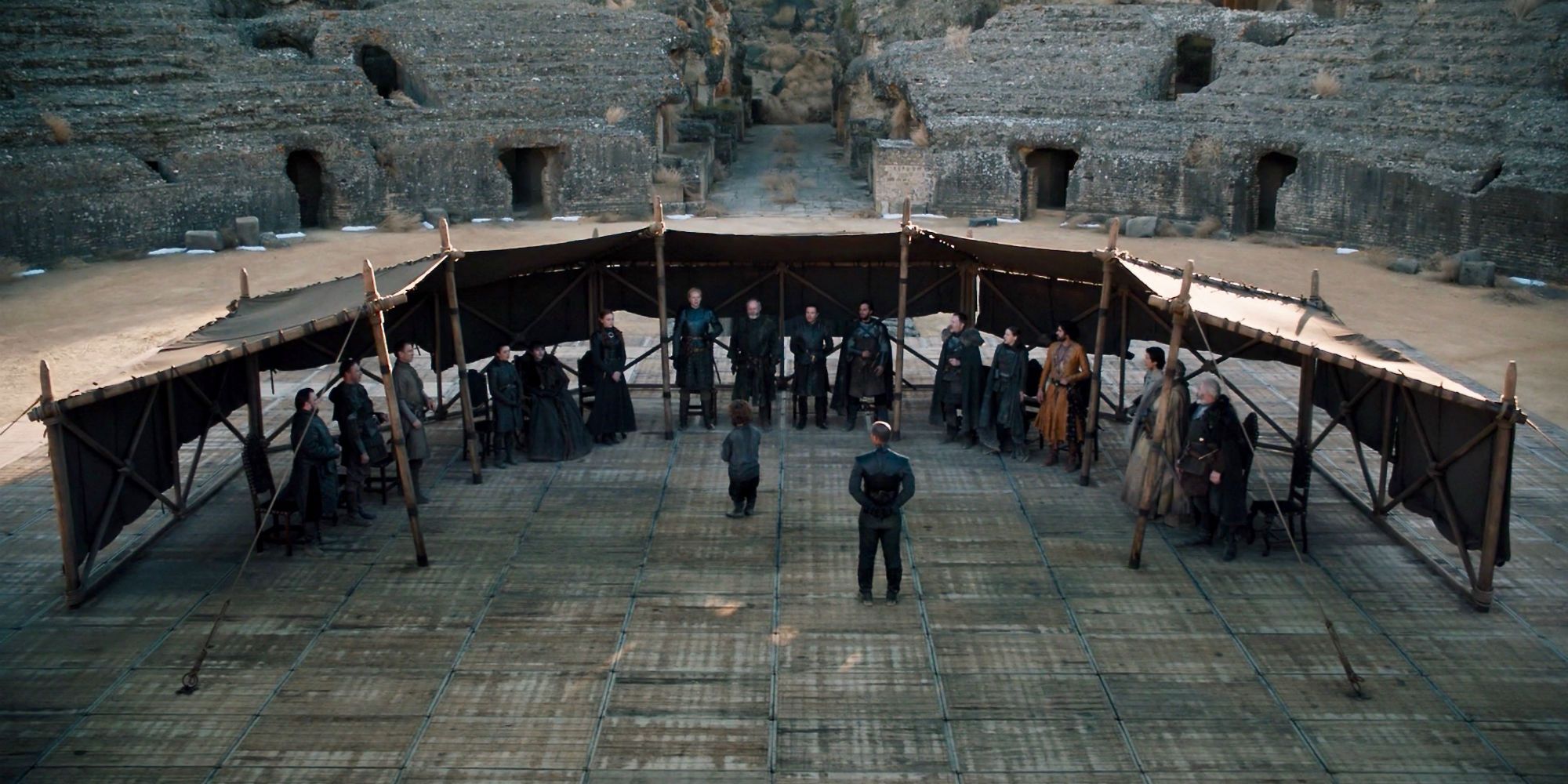

The Great Council Solves Game Of Thrones’ Political Situation

Another major accomplishment of “The Iron Throne” was the development of the Great Council and the abolishment of the absolute monarchy and succession laws that heretofore governed the country. While Game of Thrones has been less explicit about this particular theme (especially given HBO’s season 8 choice of marketing hashtag #ForTheThrone), it’s clear that Westeros had suffered mightily under the long-standing system of government. It was that system that placed a mad king with a taste for wildfire on the throne with no one able to legally oppose him. Robert’s Rebellion, which rose in response to that, wasn’t the realm’s first civil war; it wasn’t even its second or its third; and unfortunately, it wasn’t its last.

The War of the Five Kings was arguably one of Westeros’ bloodiest and most-prolonged, but it seemed, for a while, that the realm could be healed if the right person sat the Iron Throne. Yet how does one find the right person when the line of succession is as muddied as it was in season 1. There were valid claims coming out of the woodwork and each one had an army to back it. Stannis might have brought some lasting peace, but such an intractable ruler would’ve alienated enough people to make him friendless, and before long he would’ve governed by fear just like Dany. The people accepted Joffrey as their king because the truth of his paternity didn’t matter as much Ned or Stannis would’ve hoped, but he was, for obvious reasons, a worthless ruler who did more damage in his short reign than his father. Tommen was so successfully manipulated by everyone around him he couldn’t have made for a competent decision maker no matter how kind and gentle he was. And Cersei was so selfish it’s doubtful she ever bothered with making a single policy decision that wasn’t rooted in her own bitterness and desire to protect what little was left of her family and name.

The problem of absolute, successional monarchy seems obvious to modern audiences used to the idea of democracy and the distribution of power via some kind of system of checks and balances. Game of Thrones spent seven bloody seasons showing why such systems of government rose up in the first place. Quite simply, the idea of placing absolute power in the hands of one individual because they were either born into it or took it by force presents a host of problems that mostly victimize those who had no role in choosing a leader in the first place. Varys was so committed to finding the right person to sit the Iron Throne in the name of the smallfolk that he’d watched suffer under Aerys, Robert and a handful of others. But his lack of vision when it came to eliminating the idea of succession altogether eventually wound up getting him killed when he realizes he’s backed the wrong person, yet again, and his convictions force him to act, despite it putting his life in danger.

It might seem like pie-eyed optimism for Sam and the others to attempt some kind of conciliar government that takes succession out of the equation and spreads power out a little more evenly. There are potential problems with that idea down the road. What if the council can’t come to an agreement? What if someone else with a lust for power and the armies to back it up decides to lay waste to the council in the future? But Game of Thrones needed to address the fact that the Westerosi system of government made it far too easy for tyrants and violence to run rampant, and as the saying goes, Rome wasn’t built in a day. What we saw at the end of “The Iron Throne” was the necessary first step toward creating a better future for the remaining six kingdoms by abandoning a system that had proven faulty time and again for centuries.

Why King Bran the Broken Makes Sense For Game Of Thrones

The choice to place Brandon Stark in power at the end of the series feels like one of Game of Thrones’ more contrived narrative twists. His significance has been largely shoved to the side in favor of more dynamic characters and stories, so the council choosing him at the end of everything felt a bit unearned. For whatever reason, the writers haven’t been able to communicate what he and his powers actually are beyond the ability to visit the past and possibly affect change. His scenes during the final season have mostly surrounded dire warnings about the Night King’s movements, a kind send-off to Theon and enigmatic statements he threw out here and there to anyone silly enough to try and start a conversation with someone who contained the whole of human memory.

But, again, these are problems that come down more to execution than anything else, and given the rather large pile of unearned moments in Game of Thrones season 8, it seems unfair to only look at this development solely through that lens. Especially because, broadly, it’s the decision that makes the most sense, even if it was a clunky, oversimplified ride to get there.

Because Bran can father no children and because he’s supposedly beyond the kind of temptations to power other humans would be vulnerable to, at least for the moment, he makes the best leader the realm’s seen in decades. Maybe ever. He’s also got an education in kingship that goes utterly unmatched given that he has the experience of every ruler and every event in the history of his country to use as context. He has no ego to speak of, meaning he’s in far less danger than any of his predecessors to fall victim to the manipulations of those with selfish goals, or even to his own wants and desires. And because he is one of the most physically powerless people in Westeros, he represents a values system that will, hopefully, keep those people in mind when making decisions. Is there magical thinking at work here? Sure. But if you look beyond that to the symbolism of placing someone like Bran in power, it works.

Like the new system of government that put him in power, Bran represents an unprecedented kind of leader in Westeros. There’s the problem of course, of what happens when he dies and the next leader doesn’t have the benefit of also being the Three-Eyed Raven (if Bran dies at all and if he doesn’t gift someone else with his abilities before he does so), but Game of Thrones was never going to have an ending that attempted to promise audiences that all in Westeros would live happily ever after once the series came to an end. The realism that made this show popular in the first place ensures that kind of send-off wouldn’t happen. It’s never, ever been a story about happily ever afters, as “The Iron Throne” hammered home.

This is still a realm of flawed, selfish people, hungry for power fighting against those who can see beyond themselves to affecting change for the greater good. Like the one against death, this is a war that never ends, but one that always needs fighting. But if Game of Thrones taught anything, at least it was the satisfaction that, for a moment, Westeros is free of tyrants and those in power on the new small council seem committed to not abuse it. “For a moment” is the best any of us can hope for.

Link Source : https://screenrant.com/game-thrones-finale-good-best-ending/

Movies -God of War Demake Gets Sony Santa Monicas Approval

Gilmore Girls 10 Things That Make No Sense About The Dragonfly Inn

Joffrey Baratheon vs Aerys Targaryen Who Was The Worst King In Game of Thrones

How Violent Floods Made Mars Surface What It Is Today

Hunger Games The Actors Who Almost Played Finnick Odair

Frozen II Review Disneys Sequel is Deeper & Darker If Also Messier

Humankind Getting Started Guide (Tips Tricks & Strategies)